| |

Two Christchurch schools develop teaching practices that support children with signs of dyslexia

Some children in Christchurch are coming home from school feeling happier and less frustrated than they used to be, and their parents have noticed.

Families have been telling staff at Paparoa Street School and Cashmere Primary School about the changes. It’s no coincidence that both schools are running professional development aimed at helping children who show signs of dyslexia.

Teachers there are learning how to identify and support each student’s needs. The schools are identifying dyslexic type tendencies but are careful not to label children. Rather, they treat them as individuals and provide classroom teachers with a clear process to improve how they support them.

“The feedback from parents is phenomenal because they can see that these steps are being taken at school to understand their children better,” says Raewyn Saunders, deputy principal at Paparoa Street.

|

|

|

Raewyn coordinates support for individual needs at her school. Cashmere deputy principal Cathy Andrew has similar responsibilities and they work together on professional development.

The pair travelled to the UK earlier this year in a trip supported by the Dyslexia Foundation in order to learn first-hand from schools identified as dyslexia-friendly schools by the British Dyslexia Association.

Raewyn and Cathy say since then they have moved their schools’ thinking and practice ahead. Teachers are responding positively.

“It’s working with staff in a very supportive way and getting them to buy into it,” says Cathy.

“Our staff are really embracing it in both our schools because they see that what works for these students works for all students.”

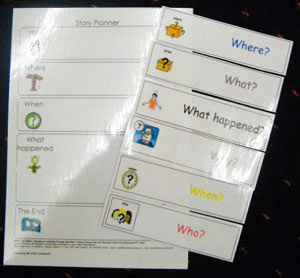

Teachers are helping students to process information better. They check students understand the key words used in a lesson and put up posters that describe what children need to do to reach the next level of learning.

They also give very specific instructions so the learning objective of each activity is understood. Each class has a visual timetable on the wall that has words and pictures.

These methods help all students become self-regulated learners, says Cathy. And as Raewyn explains, they are especially helpful for children with dyslexia.

“There’s no mystery. It’s building capability in them, so if they don’t understand something they can access the information, whether it’s through a display on the wall or teaching aids on their desk top.”

At the same time, teachers are strengthening the foundations of reading lessons. They focus at an early age on developing children’s awareness of the sounds within spoken words (phonological awareness) and the correspondence between sounds and letters (phonics) as the children read and write texts.

|

|

|

Cathy says teachers know from their own work which children are not reaching their potential. In both schools children identified as ‘at risk’ are given additional, more detailed assessment that provides specific information on where a child needs to be supported by explicit and specific teaching.

The two say the earlier this happens the better. If children are left to struggle, their self-esteem can have taken a knock by the time they finish primary school. Behaviour issues can develop.

“We have a real focus in our school on early identification and support for learning needs,” says Raewyn.

“The first line of support is mainstream teachers making a shift but there is individual support for students who need more support than a classroom teacher can provide.”

The two DPs brought back learning programmes from the UK to trial. They also came back with a good impression of schools that have created an inclusive learning culture.

At these schools, leaders drove changes and children could articulate what they were learning. Lessons were purposeful and related to children’s environments. Students were excited to be in class, says Cathy.

“There were some schools that were absolutely buzzing.”

At Paparoa Street and Cashmere, Raewyn and Cathy will continue to introduce strategies as time goes by. Cathy says it is a long-term approach and they need to fit this professional learning in with other initiatives. It’s a work in progress.

Changes in practice are focused on children’s strengths, not deficits, says Raewyn. And teachers can see there are manageable steps to making change.

“We’re just two schools that are passionate about making this shift.”

“There’s no mystery. It’s building capability in them, so if they don’t understand something they can access the information, whether it’s through a display on the wall or teaching aids on their desk top.”

|

|

|

More information

According to the Ministry of Education’s working definition: “Dyslexia is a spectrum of specific learning difficulties and is evident when accurate and/or fluent reading and writing skills, particularly phonological awareness, develop incompletely or with great difficulty. This may include difficulties with one or more of reading, writing, spelling, numeracy, or musical notation. These difficulties are persistent despite access to learning opportunities that are effective and appropriate for most other children.”

The Ministry has a booklet on dyslexia. This can help teachers to identify students’ difficulties and it describes supportive teaching strategies that build on their strengths.

http://literacyonline.tki.org.nz/Literacy-Online/

What-do-my-students-need-to-learn/

Students-strengths-and-needs/Dyslexia

Dyslexia workshops

The Dyslexia Foundation is running workshops by British dyslexia expert Neil MacKay and sponsored by the Ministry of Education next year. The workshops at the end of May and start of June will range from basic knowledge about dyslexia through to advanced strategies and techniques for working with students with dyslexia.

For more information see www.4d.org.nz/workshops/

|

|